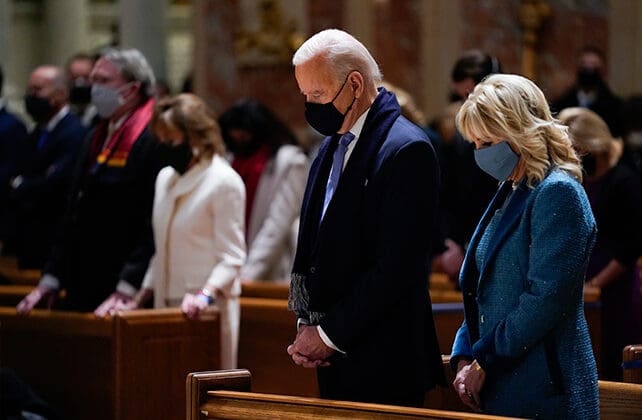

VATICAN CITY (RNS) Meeting as a body next month for the first time since a pro-choice Catholic was elected president, the U.S. Catholic Bishops Conference is expected to address at its spring general assembly the question of whether President Joe Biden or any Catholic politician who supports abortion rights should be allowed to receive the Eucharist.

But according to some observers, the controversy is less about the sacrament than it is about the lack of communion among the U.S. bishops themselves and between the U.S. conference and the Vatican.

“This is more about Pope Francis than it is about Joe Biden,” said David Gibson, director of Fordham University’s Center on Religion and Culture, in an interview with Religion News Service on Thursday (May 27). “It’s more about the future of the church than it is about Eucharistic theology.”

The Vatican and the U.S. bishops are uniform in their opposition to abortion, with Pope Francis likening getting an abortion to “hiring a hit man.” The pope’s vocal opposition to abortion, which he calls “a grave mortal sin,” is often quoted by prelates who object to administering Communion to pro-choice political leaders.

The division between the Vatican and the American bishops is not about content, then, but method.

In almost all matters, Francis is an advocate for the winding and difficult path of dialogue and discernment, an approach reflected in a letter sent May 7 from the Vatican’s doctrinal watchdog to the president of the U.S. Bishops’ Conference, Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles, as the issue of denying Communion to pro-choice politicians heated up.

Cardinal Luis Ladaria, the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, called on the bishops to hold an “extensive and serene dialogue” among themselves, while reaching out to “engage in dialogue” as well with Catholic politicians who hold pro-choice positions. The bishops should make “every effort,” the letter said, to take into account the global context of the church.

Only then, Ladaria wrote, would bishops “face the difficult task” of deciding what course of action will benefit “the grave moral responsibility” of the local church. After achieving “true consensus,” the U.S. bishops might issue a statement on the matter, the cardinal continued, while recognizing that even then “it could have the opposite effect and become a source of discord rather than unity.”

Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone of San Francisco and Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila of Denver, who have both pushed for the Communion ban, agreed in a May 25 statement on the need for “serene dialogue.” But likeminded commentators say that given the church’s stance on abortion there isn’t much left to discuss.

“There is little that is unclear here, and further “dialogue” is not going to clarify much of anything,” wrote George Weigel, papal biographer and distinguished senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, in the conservative magazine First Things.

But some influential prelates who are considered close to Francis seem to feel that there is so much to discuss about “Eucharist coherence” that they’ve argued to delay any dialogue until the conference can meet in person: June’s general assembly will be held over Zoom to avoid the risk of COVID-19. In a May 13 letter, 67 U.S. bishops, including Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston and Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, called for a delay.

Cordileone, Aquila and other conservative bishops have objected to a delay, a sign that proponents of a ban are ready to risk public disagreements. This faction is “very explicit that doctrinal purity is greater than church unity,” Gibson said, adding that some members of the U.S. episcopacy “want to create pressure and draw a line in the sand.”

Pope John Paul II and his successor Benedict XVI could count on the obedience of the bishops across the Atlantic — not least because they appointed most of them. Francis is finding that their fealty is to doctrinal positions rather than the seat of St. Peter itself.

“Clearly in the past eight years, if there is one church that has given trouble to Pope Francis directly and openly it’s the U.S., there’s no question about that,” said Massimo Faggioli, professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University, on Wednesday (May 26).

According to Faggioli, bishops appointed by Francis, still a small minority, often find themselves “outnumbered and outmaneuvered.” What remains to be seen is what the “silent majority” of bishops will do when the time comes to make a decision in June, Faggioli said.

Regardless of what the U.S. bishops decide, the Vatican has made no secret that it looks forward to close ties with the Biden administration. “I think Biden and the White House have a relationship with the Vatican that does not run through the offices of the USCCB,” Gibson said.

Biden and Francis will likely meet in the coming months, as the pontiff has signaled that he may attend the COP26 environmental summit in Scotland in November. The following month, the G20 meeting of developed nations will be held in Italy, providing another opportunity for the two to talk.