Ryan Burge, Eastern Illinois University

The Southern Baptist Convention will convene its annual meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, on June 15, 2021, in what could be the most consequential such get-together in recent memory.

Just 15 years ago, the SBC boasted some 16.3 million members across the United States. However, it is hemorrhaging members. According to data released in May, Southern Baptists have lost over 2 million members since 2006, with over 400,000 defections in the last year alone.

The denomination has also been embroiled in a number of controversies in recent years. A resolution passed at the 2019 meeting condemned critical race theory, a set of ideas that view racism as structural rather than expressed through individual prejudice, prompting several prominent Black pastors to depart. And in March, Beth Moore, a very popular female Southern Baptist author and speaker, publicly announced that she was leaving the group, citing the SBC’s approval of Donald Trump and its views on gender. The widely held perception is that the SBC has lurched farther to the right over the last few years.

As a result, all eyes will be on the resolutions that are debated and subsequently passed at the annual meeting, the belief being they will give tremendous insight into the trajectory of the SBC and more generally American evangelicalism, of which Southern Baptists are the largest group.

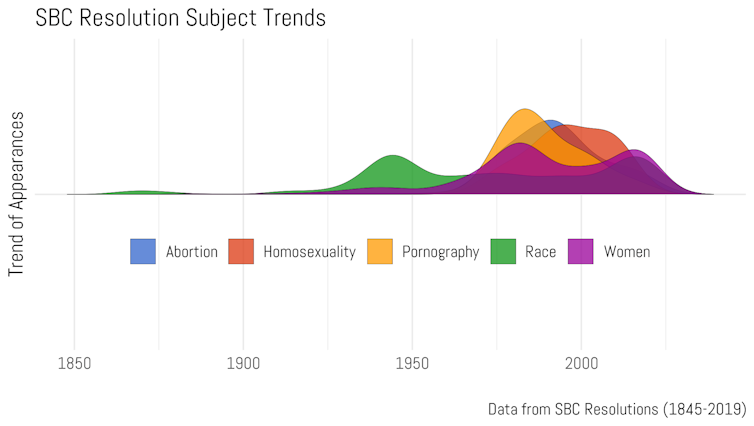

I’m a religion data analyst who wrote a computer script to collect and organize the text of all the resolutions passed at the annual meeting data back to 1845 to see if there were any patterns. What became clear was that many of the “bread and butter” culture war issues that fueled the SBC 20 years ago – such as abortion and homosexuality – have faded and been replaced by a new set of issues that seem to be furthering the divide between conservatives and more moderate members of the Southern Baptist Convention.

One thing to note is that for the first 100 years of the convention, which was formed in 1845, the culture wars that dominate the conversation today were largely absent. The discussion concerning race began only in the 1940s, but that quickly ebbed a decade later.

In the 1970s, the annual meeting began to turn to concerns about abortion and how that affected women in the United States. In the early years after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, many resolutions that discussed abortion also contained the word “women.”

But that linkage began to weaken by the late 1980s. Discussion around abortion peaked in the mid-1990s, which is right about the same time that topics concerning homosexuality were being discussed with greater frequency.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

But in the last 10 years, there’s clear evidence that the classic culture war issues of abortion and homosexuality have faded. In fact, the word “homosexuality” has not appeared in a resolution since 2013. In their absence, race and gender have become much more central to the debate. Pornography – a hot resolution topic during the 1980s when the pornographic industry was experiencing a boom – no longer registers as a concern worthy of registering in a resolution.

The last meeting of the SBC occurred in 2019, and there was both a resolution on women not being included in the selective service, which would determine who would be eligible for a military draft in the U.S., and one against the teaching of critical race theory.

There’s ample reason to believe that both the role of women and race will be on the minds of the attendees next week, given the amount of media coverage to the topics in the runup to the event.

The trajectory of evangelicalism hinges in part on what resolutions get debated at the annual meeting and which ones eventually pass. Is the solution to a rapidly declining membership becoming more theologically and ideologically conservative? Or is a more inclusive SBC the remedy to this downturn?

The annual meeting might deliver a clearer picture of where members of the SBC see the future of the denomination.![]()

Ryan Burge, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Eastern Illinois University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.