By ELANA SCHOR, LUIS ANDRES HENAO and JESSIE WARDARSKI Associated Press

NEW YORK (AP) Yehudah Webster, wearing a neon vest with an “Election Defenders” tag around his neck, started his Tuesday outside a Brooklyn polling place. Only the gray yarmulke Webster wore hinted at his specific role: faith-based observer on a uniquely anxious Election Day in America.

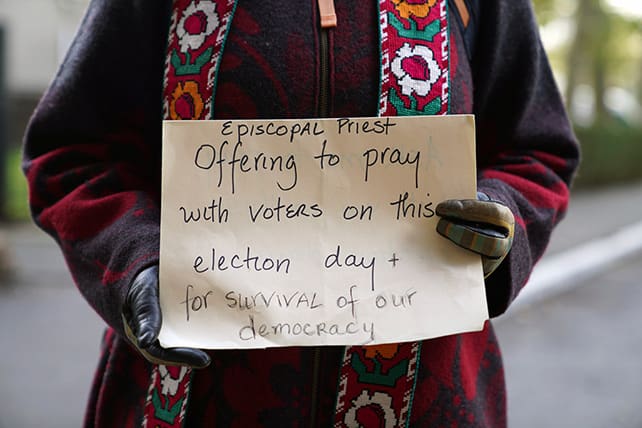

Webster, an organizer with the progressive group Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, is part of a broader network of faith leaders fanning out to the polls nationwide – to support voters by providing a peaceful presence and, if necessary, defusing any tense moments. The religious community’s engagement on Election Day goes beyond physical attendance at the polls, too, with other clergy offering up public prayer for an unobstructed electoral process.

That faith-motivated witness of the nation’s ballot-casting follows a presidential race that saw both parties’ nominees focus intently on outreach to religious voters, from Roman Catholics in the Rust Belt to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Arizona. But the red-blue divide that dominates every Election Day was far from the minds of most spiritual leaders who showed up, regardless of the denomination or tradition they represent, to bolster the free exercise of voting rights.

Webster described his mission as “creating supportive and safe conditions for voters,” adding that he and other faith-based polling counselors have adopted “an approach of nonpartisan and multi-faith reverence, and not trying to come with an agenda or push any faith on any person.”

The Rev. Liz Edman, an Episcopal priest and poll chaplain shared the sentiment as she blessed voters outside a polling station in Harlem.

“For many people voting is a spiritual matter,” Edman said. “And I don’t mean their opinions, that’s a political issue for them. What I mean is standing up, taking responsibility for our role in our country, being accountable for the community in our county – that’s a spiritual experience.”

William Green, associate pastor and director of discipleship at Foundry United Methodist Church in Washington, described his own plans to “simply be present” in the streets of the capital as unrelated to which party wins or loses.

“It’s not a partisan witness,” Green said. “It is a witness for national unity.”

Given the active threat of the coronavirus, Webster and others trained to play supporting roles at polling places offer face masks, gloves and hand sanitizer to voters. Yet it’s their other job, to help de-escalate in the event of problems, that is getting outsized attention amid worries about potential voter intimidation, especially in swing states.

In nine of those battleground states, the Lawyers and Collars initiative – part of a partnership between multiple faith-based and civil rights groups – has signed up more than 100 religious leaders to serve as poll chaplains at more than 60 voting sites. The initiative also partners faith leaders and lawyers at polling places considered particularly vulnerable to disruption.

“We’ve never done it at this level before,” said the Rev. Barbara Williams-Skinner, CEO and co-founder of the Skinner Leadership Institute, which is spearheading the effort with the Christian social justice group Sojourners and the National African American Clergy Network.

On Tuesday, Williams-Skinner said poll chaplains would be given a face mask with the logo of the group, so they can be easily recognized; a list of instructions; and a toll-free number to report any attempted intimidation or irregularities.

The Rev. Alyn Waller, senior pastor of Enon Tabernacle Baptist church in Philadelphia, joined the nationwide effort for the first time this year, after encouraging people to vote and been a regular poll observer since 2008.

In 2020, Waller said, “the stakes are a little higher this time.”

On Election Day, he started monitoring at dawn in front of his 5,000-seat megachurch and then visited precinct chaplains at 15 polling stations across the city.

So far, he said, the voting has been carried out peacefully. “We are optimistic that nothing has happened thus far, but we’re going to be vigilant for the rest of the evening,” he said.

At least 98.8 million people voted before Election Day, about 71% of the nearly 139 million ballots cast during the 2016 presidential election, according to data collected by The Associated Press. Given that a few states had already exceeded their total 2016 vote count, experts were predicting record turnout this year.

Not every person present from the faith community was a poll chaplain. Some showed up to pray for an unfettered Election Day. Others offered public support from afar: The Rev. William Barber, for instance, a leading liberal pastor who co-chairs the Poor People’s Campaign, livestreamed a prayer service from the steps of a church in Washington. Barber is also expected to host a Wednesday call with Sister Simone Campbell, a progressive Catholic social justice activist leader, to discuss the status of election results.

More conservative-leaning faith leaders and advocates were preparing their own message for Election Day as well. The Revs. Harry Jackson and Jack Graham were among evangelical allies of President Donald Trump who joined a livestreamed prayer event hosted Monday night by the Christian nonprofit My Faith Votes.

The Rev. Mariann Budde, bishop of Washington’s Episcopal diocese, said what’s at stake in the vote goes beyond mere partisan politics to touch on broader issues such as health care availability during the pandemic.

“Christians line up on the partisan spectrum wherever they line up, but these are gospel issues,” Budde said.

The Episcopal Church hosted an online training last month focused on civil discourse, and its presiding bishop hosted a Sunday interfaith prayer service joined by Jewish, Catholic, Sikh and Muslim leaders.

In the swing state of Florida, retired Episcopal bishop the Rt. Rev. George Young prayed before heading to the polls on Tuesday, wearing a white collar and a cross. Young said by phone that he hoped to offer a “calming and peaceful” presence outside polling places and to be available for any prayer requests.

Like many playing a similar role, Young said the presence of a faith leader at the polls might deter anyone seeking to intimidate voters.

“Whether it happens or not,” Young said, “many people are anxious.”

___

Schor reported from Washington. Associated Press reporter Mariam Fam contributed from Winter Park, Fla.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through the Religion News Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

This article originally appeared here.